The eighteenth century saw a massive shift in the reforms of punishment. Instead of being motivated by a concern for the welfare or benefit of prisoners as members of the society, people sought to make power operate more efficiently, calling for theatres of punishment as an obstacle to lawbreaking. Taking inspiration from the classical age, Michel Foucault, in his book Discipline and Punish, uses the body as a target of power to form the basis of his argument: a docile body is to be subjected, transformed, used, and improved, implying a new scale of control. This new modality of control revolves around never-ending, continuous coercion, which is exercised with respect to a codification that partitions time and space. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, control over the economy of the body was solidified as a general formula for domination. The disciplinary institutions of the time began to shape the political autonomy of the body and define the mechanics of power within a changing world, as the exercise of punishment swivelled from mindless torture, public theatrical spectacles of gruesome violence, substantial force, to the forces of discipline and control, as a way of controlling the operations, positions, and activities of the body.

Foucault’s work forms the edifice of the penal institutions as we see them today. He argued for the importance of the technology of time, and the regulation of an individual’s time, which is attributed to the disciplines of the individual – discipline doesn’t regulate time in the same way that handheld alarm clocks do, but focuses more on the political technology of an individual’s time, wherein time is divided like space. Space and time form one of the most fundamental aspects of the effectiveness of a basic disciplinary system, predominantly because they are the most basic elements of human life. Discipline, in this aspect, is essentially the segmentation of a convict’s day into hourly blocks, for example, in line with an exhaustive plan. In fact, Foucault’s very idea of human and societal progress during the Enlightenment is attributed to the development of prisons, timetables and other technologies that help to bring about a widely accepted definition of the structures of power. For Foucault, the key shift came about when exercise, such as prayers for salvation and military drills, became instruments of control instead of instruments to better oneself.

The prevailing worry that hangs over the 21st century and lends cadence to contemporary appeals for liberation and escape from the rat race is the fear of being just another ‘cog in the machine’, which was an idea propounded by Foucault to be engrained in the penal code. This notion was based on his argument that the individual is created from the group, and the individual can only exist in massive groups, which at the time, was extremely contradictory to the orthodox philosophical view of the creation of society, which held onto the utopian ideal that society is built upon a social contract or agreement between men who give up some of their birthrights of retribution to the penal institutions in order to live in harmony. However, according to Foucault’s opinion of modern society, you do not ‘choose’ to enter society through a contract, but it controls you completely through technology and power.

Foucault’s negative conception of individuality is crucial to this analysis – while commercial advertising and the mass media tends to emphasise on consumerism as an avenue to reach individuality, and the general concept of wanting to be unique and separate from the crowd has been a recurring theme through this century, for Foucault, the individual is a potentially dangerous device restricted by power. The more abnormal and excluded one is, the more individual they become.

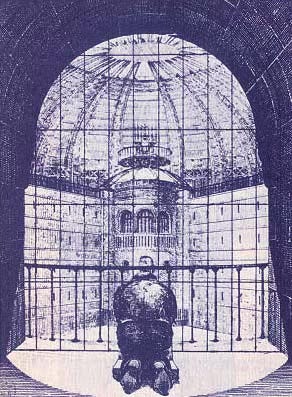

The art of punishing transfers individual action to a whole, differentiating individuals from one another by means of a rule that is also the minimum of behaviour, inspecting individuals and allocating them ranks within a hierarchical system, thereby tracing the abnormal. Disciplinary mechanisms create a ‘penalty of the norm’, revolving around the idea of the ‘normal’, one of the greatest instrument of power that emerged at the end of the classical period, where the idea of belonging to a ‘normal’ group slowly served to displace indicators of status and hierarchy. Normalisation does not only engender homogeneity, but it is also this very homogeneity that makes it possible to measure differences between individuals, leading us to the concept of ‘Examination’, which represents the strategies of an observing hierarchy, transforming the economy of visibility into the exercise of power – each individual becomes a ‘case’ to be analysed and described. This notion leads us to the constitution of the individual as an effect and an object of power.

This brings us to a rather more coherent definition of the aims of the prison system, offering us a lens to evaluate its merits and demerits. The criticisms of the prison system has gone through many a metamorphosis and yet the underlying tenets of the argument remain unchanged – prison is a great failure of penal justice, because prisons have not always been successful in diminishing the crime rates, detention has been known to cause recidivism, the harsh environment and numerous constraints of the prisons may produce delinquents, prisons allow delinquents to associate, conspire, and plot future criminal activities, the state of freed inmates is often one of greater surveillance and more often that not, future recidivism, and prisons nearly always end up impoverishing the prisoners’ families by incarcerating the primary breadwinner.

However, Foucault argues that we must not think of the establishment of the prison, its failure, and its reform as three disparate stages, but we must consider the prison to be a system imposed on the juridical deprivation of liberty, known as the ‘carceral system’. The failure of the prison is the remedy – the carceral system aims to reorganise knowledge about crime, not eliminate it. Foucault perceives the prison as being akin to a psychiatric hospital, identifying and isolating the ‘abnormal’ or illegal elements of society. Foucault does not argue that prison is responsible for creating crime, but that without prisons, the crime and criminal would be perceived in different ways, making the prison an essential institution and building block of society. Proposals for the abolition of prison fail to understand the scale, the very extent at which it is embedded within society, forming an integral chokepoint in the nexus of power that spreads through society. In its failure, it succeeds.